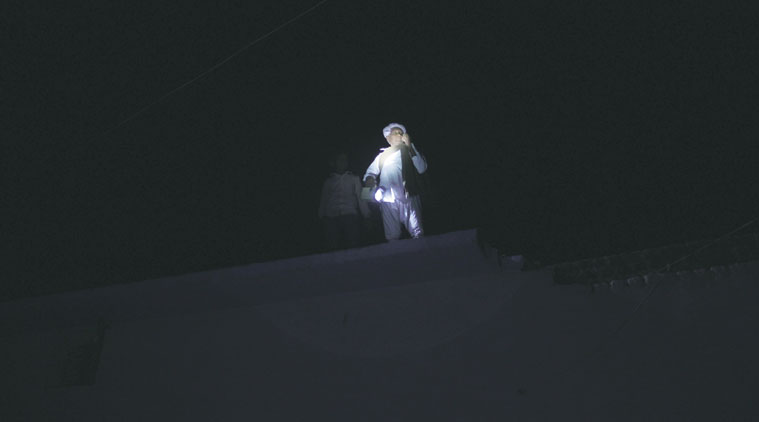

A watch-tower in Dhudhala village of Jafrabad

A watch-tower in Dhudhala village of Jafrabad Chaggan Akbari of Bhad, who has stopped taking out cattle after dusk.

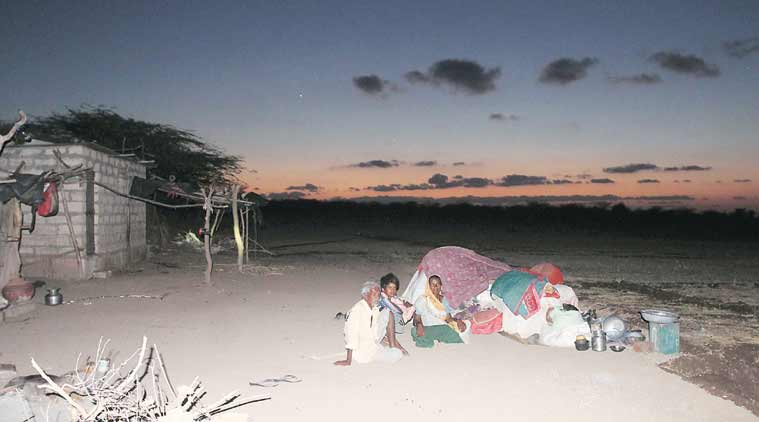

Chaggan Akbari of Bhad, who has stopped taking out cattle after dusk. Maniben Parmar, mother of Bhura, who was killed and eaten by a lion in 2012.

Maniben Parmar, mother of Bhura, who was killed and eaten by a lion in 2012. The Parmars dread the night at Ambardi, located next to Gir forest area

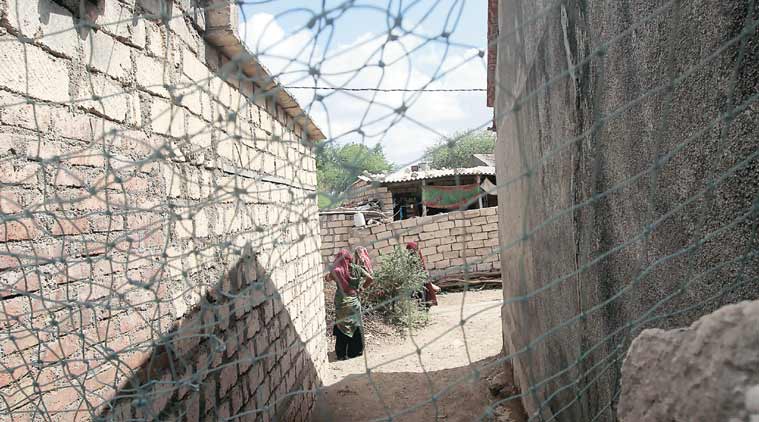

The Parmars dread the night at Ambardi, located next to Gir forest area Fences are up in Jafrabad’s Jikadri village

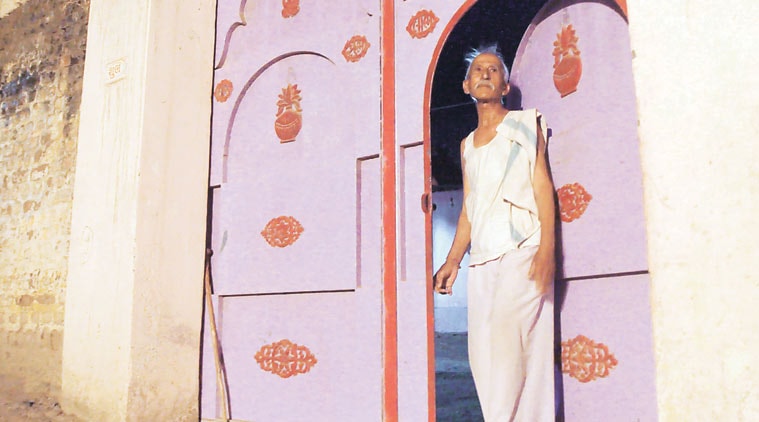

Fences are up in Jafrabad’s Jikadri village Retired teacher Kanji Bagda says he now keeps his cattle locked up inside home.

Retired teacher Kanji Bagda says he now keeps his cattle locked up inside home. A lioness with a cattle kill. Villagers talk of them coming into houses to attack

A lioness with a cattle kill. Villagers talk of them coming into houses to attack

Villages around Gir have long lived with the big cat. However, while in 23 years, there have been 18 fatal lion attacks

here, six have been reported in five months of 2016 alone.

Photographs: Javed Raja

Gopal B Kateshiya

Updated: June 12, 2016 1:13 pm

As the sun pales on a sweltering summer day, sharecropper Raju

Charola, 33, his wife Champa and mother Labhu quickly tuck into their

dinner of potato curry, chapati and mango pickle, inches from their

makeshift chullah, at a farm in Ambardi village in Dhari taluka of

Amreli.Darkness descends quickly, with the eight-hour agricultural power supply to these parts snapped at 7 pm. The water of the Shetruji river laps nearby, but the three hold their ears out for what lies just beyond — the 400-hectare dry deciduous wilderness of Ambardi reserve forest in Gir East, where lives the only population of wild lions in the world outside of Africa.

It’s Raju’s sister Nandu, 55, and husband Pancha Parmar, 60, who look after this farm. However, Raju, Champa and Labhu have abandoned their own hut in the neighbouring farm and moved here for the past few days, since teenager Jayraj Makwana was mauled to death by allegedly a pride of Asiatic lions, a few fields away.

The attacks in Gir East have occurred in the Ambardi-Bharad group panchayat area. All the three victims were labourers. While Jayraj (14) was killed on May 20, Labhu Solanki (60) was attacked on April 10. The death of Zeena Makwana (54), killed in Ambardi on March 19, has worried experts, as reports indicate he had been eaten by the lions, which is extremely rare.

Following the incidents, for the first time in Gir’s history, a pride of lions, including 13 members, was caged. A number of labourers have fled the farms surrounding Gir. Former state agriculture minister and senior BJP leader Dilip Sanghani, a native of Amreli, has written to the state forest minister demanding that farmers be allowed to shoot lions and leopards in self-defence.

***

The Gir protected area, consisting of Gir National Park and Sanctuary, Paniya Wildlife Sanctury and Mitiyala Wildlife Sanctuary, is spread over 1,412 sq km. As per the 2015 census, it has 523 lions. But a number of them now live outside the protected area.While the Forest Department has been preparing the Barda Wildlife Sanctuary in Porbandar district, west of the Gir forest, as a possible second habitat for lions for years, the growing carnivore population has moved east to Amerli and Bhavnagar districts. Forest officers estimate that lions now roam an area of 22,000 sq km.

In fact, the discovery in 2001, during the five-yearly census, that a few of them had settled permanently in Paniya area of Amreli had been a cause of much elation. The development marked a paradigm shift, indicating that the lions had set out to recapture lost territory after once being reduced to a few dozen prides in ravines deep inside the Gir forest.

Now this spectacular comeback is posing new questions, including for people of the area, such as Raju and family.

Since the 2001 census, the lion population in Amreli has increased leaps and bounds, to 174 by 2015, with lions being sighted in five of its 11 talukas. For the territorial animals, forest officers say, Amreli’s hillocks and the plains of the rivers Shetrunji and Dhatarwadi, covered with thickets, offer a good habitat. Apart from a source of water in the summer, the rivers also draw nilgais (blue bulls) and spotted deer — a natural prey for the lions.

In the 2015 census, only Junagadh had better lion numbers, at 203, of all the four districts where the big cats have settled: Junagadh, Gir Somnath, Amreli and Bhavnagar.

Besides, of the 174 lions counted in Amreli, 45, or a little over 25 per cent, were found to be living in revenue areas — agricultural fields, villages and other areas of human habitation and activity. Again, only in Junagadh, do more lions (58) roam in revenue areas than in Amreli.

Across the four districts now, the rising number of lions and their appearance in villages is a common story.

After the 2015 census revealed that 167 of the total 523 lions were living in revenue areas, the state government had formed a task-force for a management plan. The task-force has submitted its report, but its recommendations, including for a unified forest area, say sources, remain under “consideration”.

***

Raju’s fear notwithstanding, his brother-in-law Pancha points out that living next door to the big cats had never bothered the villagers, till now. “Lions are very sensible animals. They always respect our warning calls while they are on our fields. They would never attack a human being. I believe they must have been very hungry when they killed that boy (Jayraj),” says Pancha, who is illiterate.The two-hectare farm he has been cultivating in Ambardi village for the past five years with wife Nandu is owned by Shantibhai Dobariya. Only two unfarmed fields, now run over by bushes, separate Dobariya’s farm from the reserved forest.

Ambardi has a population of around 1,800, a majority of them farmers. The Shetrunji river ensures rich harvest and almost every other landlord in the village engages labourers. It is these labourers who have fallen victim to lions.

Pancha’s native village Vekariyapara nearby is also part of lion territory. He talks of how, while other farmers complain of nilgais and wild boars destroying their cotton and groundnut crops, he has never faced such a problem due to his feline neighbours. “As the big cats do their rounds here, no other animal dares step in. One can grow as much crop as one wants,” he smiles.

Pancha, however, says all this comes with proper precautions. “If a lion enters my wheat field at night, I cannot irrigate the crop. So we switch off the motor-pump and go to sleep. Even if the next morning the landlord scolds us,” he says.

“Lions started visiting our village 15 years ago. Since then, farmers have stopped working on their farm at night unless unavoidable,” says Ramku Varu, sarpanch of Dholadri village in Jafrabad taluka, around 50 km away.

Bhawan Gohil of Jikadri village in the same taluka, who has 125 goats and sheep, says he is reconciled to losing three-four of his animals to “savaj (lions)” every year. “They even jump into the verandah and raid my herd in our presence,” Gohil says. According to Gohil, even taking his herd for grazing has been getting more difficult.

“But I have no complaints. Lions take their share as alert as I may remain,” he says with a mild smile.

There are 54 colonies of maldharis or cattle herders, traditional forest dwellers, inside the Gir forest.

The Forest Department gives Rs 1,000 as compensation for a goat or sheep killed by a wild animal, Rs 10,000 for a killed bullock and cow and up to Rs 20,000 for a buffalo.

***

Still, the recent incidents have shaken this equanimity, particularly reports of lions eating humans. The three deaths in Gir East followed a similar pattern — lions attacked people sleeping out in the open and in the wee hours of the day.Ambardi village sarpanch Najabhai Javandhra admits things have changed. The population of lions has seen a “huge jump over the past five years”, he says. “Labourers are fleeing.”

Pancha’s own sons have survived attacks by the wild cats but no one has heard of lions eating people before. Pancha’s teenage son Ghugha, who is idling on quilts heaped in a corner, was attacked by a lioness last monsoon on the same farm where they are currently working, but escaped with minor claw marks as the family dogs raised an alarm. Pancha’s elder son Magan was attacked by a leopard a few years ago.

Raju, who also grew up next to Gir in village Dalkhaniya, says he had no choice but to move in with his sister. “The lions come near our farm to drink water. We spend nights at my sister’s place and work on our farm during the day,” he says.

Gohil’s grandfather Devshi talks about the old times when he would leave his herd without an enclosure. “They would rest in the open, even at night. But now despite creating enclosures, lions are killing our animals. The only option now is to keep our goats inside our living rooms.”

Vipul Bagda, a 30-year-old lion attack survivor from Nava Agariya village in Rajula taluka, is now too scared to cross the border of his small farm, on the banks of the Nahyo rivulet. He, his cousin Dipak Babariya and three others were chased by a lioness when they got too close to her cubs in March 2014. His cousin was killed, while another of his friends was injured. “I managed to climb up a neem tree. I was rescued after three hours,” he recalls. This lioness and her two cubs were caged after two-week-long efforts.

In Dholadri village last year, a pride of lions raided and killed seven stray cows in one go. The village had also reported a lion attack, and the eating of a body, back in 2012. Bhura Parmar, a diamond-polisher based in Surat, had been home due to a slump in the industry when he was killed.

Residents of Bhad, a village on the border of the Mitiyala Wildlife Sanctuary, around 50 km from Amreli, have raised compound walls around their homes now, which are 10 feet or higher.

“Over the last five years, lion movement has increased greatly. I used to take my cows and bullocks for grazing at 4 am. But now, it’s too risky to venture out before daybreak,” says Chhagan Akbari, a farmer.

However, the 65-year-old, adds, “Lions become violent only if harassed. I don’t bother them ever and they silently cross my field.”

Pancha, a lion veteran of as many years, also tries vouching for the animal again, saying lions generally leave if chased away with shouts and thumping of sticks. However, he is shouted down by his own family. Says wife Nandu, “The sight of the lions at night leaves me petrified. I am as jumpy as my goats inside the cottage.”

Raju wishes for something more substantial, like an axe, for protection. “But forest guards would suspect we are going to cut trees.”

***

Govind Patel, the former chief wildlife warden of Gujarat and former member of the National Board for Wildlife, says the problem is an “acid test” for the state. “Gujarat has never faced such a situation when lions have killed people and allegedly eaten them. Lions and maldharis have lived together inside Gir for centuries,” he says.What has clearly changed is the growing lion population. As Patel says, “A lion pride requires, on an average, 40-50 sq km of area as its territory. Gir can accommodate only 270 lions. Therefore, new prides have made their homes outside the protected forest. We had floated the idea of developing the region as a Greater Gir Area.”

The Gujarat government has steadfastly opposed proposals to translocate the animals, despite a Supreme Court ruling against the state. The idea was first mooted when the lions existed in a sub-population in Gir and wildlife experts feared that any disease or natural calamity could wipe out the entire species.

In 2013, the apex court gave Gujarat six months to begin the process to transfer lions to the Kuno Palpur Wildlife Sanctuary in Sheopur district of Madhya Pradesh. A committee was formed by the Centre, and the matter is still at the “planning stage”.

Early this year, Union Minister of State for Environment, Forest and Climate Change Prakash Javadekar said that the translocation would take about 25 years as lions would have to be moved in phases.

In another statement, in the Rajya Sabha last month, Javadekar said Gir had seen 91 lion deaths in 2015, compared to the average of 75 the previous two years. He said both natural and unnatural reasons had seen a rise, and that one of the reasons of the unnatural deaths was lions “falling in open wells in revenue areas”.

Gujarat is now constructing parapet walls around open wells, the minister said, as well as fencing accident-prone railway track stretches in Amreli.

Jamal Khan, Gujarat’s Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife), warns against any quick conclusions for the lion attacks. Pointing out that Amreli has seen more deaths compared to Junagadh, which has a larger lion population in the revenue areas, he says, “The spurt as well as lions eating humans are very unusual. But there can be multiple reasons. One can be low availability of food, another could be the weather (the hot temperatures making lions irritable). Also, the incidents in Dhari (Amreli) have happened on the border of the forest. Lions are new to the area. Similarly, these animals are new for people too. So each feels the other is encroaching on their territory. There is no problem in Junagadh because lions have been there for centuries.”

Forest officers also note that those who have been attacked were labourers sleeping in the open, on the ground.

While acknowledging the “growing population of lions”, Aniruddh Pratap Singh, Chief Conservator of Forests, Junagadh wildlife circle, says, “A human being sleeping on the ground and wrapped in a quilt or shawl is confusing for the lions. At night, lions see almost every object as black. Many labourers come from areas which are not lion territories and therefore don’t understand lion behaviour. But those from the lion range also seem to be careless and negligent. We have written to village panchayats scores of times, held meetings with villagers and announced over loudspeakers that people must take basic precautions like not sleep in the open and on the ground etc, but still this keeps happening.”

Apart from loudspeakers mounted on vans informing villagers of the do’s and don’ts of living in lion territory, the Gir West division has distributed pamphlets among locals educating them about lion behaviour and the precautions to take. But with electricity cut in most areas at night and temperatures high, sleeping in the open remains attractive.

Forest officers also say the smell of non-vegetarian food draws the big cats, including leopards, to human habitations.

Other officers blame provocation by humans. “Unless harassed, lions never attack humans. All the incidents have taken place at night, so, we don’t know the circumstances. The heat could also have a role. In such a state, even minimal provocation can be costly,” says T Karuppasamy, Deputy Conservator of Forests of Gir East.

Hridaya Narayan Singh, a retired social researcher of Jawaharlal Nehru University who was one of the first people to study co-existence between maldharis and lions, also says human role shouldn’t be ruled out. “Lions by nature are neither maneaters nor do they prefer cattle normally. The fact that maldharis have been living with lions inside Gir for centuries proves this. The attacks could be due to some disturbance or human interference,” he says.

Ambardi sarpanch Javandhra blames “outsiders” who come to Ambardi to see lions — or what the locals have dubbed “lion shows”. “Because of the Shetrunji river, it is easy to locate lions. However, some of them harass the lions by chasing them with cars or ramming their vehicles into animals. While the outsiders leave, the agitated lions attack locals afterwards,” Javandhra says.

There have been instances of visitors throwing stones at lions or trying to get too close to them. Some try to click selfies.

***

In case of the recent killings, the first lion was caged days after it had killed Makwana, and sent to a rehabilitation centre in Sasan after excreta analysis confirmed it had eaten the man. A lioness was caged after Labhu Solanki’s death too but she has been since then let out in the wild as her stool samples did not contain any trace of human flesh.Then, after Jayraj’s death, 16 lions, 13 of them from a single pride, were removed from Ambardi and caged at the Jasadhar animal care centre near Una in Gir Somnath district. Forest officers await laboratory results to determine if they had eaten the boy.

Ravi Chellam, a wildlife biologist and conservation scientist who is a member of the expert committee set up by the Centre to oversee the translocation of Asiatic lions, hopes the current panic doesn’t lead to any drastic steps. “Indians tolerate wildlife and celebrate nature. So you cannot take the strict position that lions and tigers should exist only within protected areas. That will be disastrous. There are bound to be problems, but you need to put them in context. The number of people knocked down by cars in a city is far more than the number going to be killed by lions in a year. That doesn’t stop us from stepping onto a road,” he says.

Bhushan Pandya, a member of the state board for wildlife who has documented the Gir forest and its wildlife for decades, also cautions that the “circumstances” of the lion deaths should be looked into first. “These are stray incidents and don’t point to any change in the behaviour of lions. Lions don’t become man-eaters by such incidents,” he says. Advising the Forest Department to not let the incidents pass without properly investigating the causes, he adds, “Just imagine if the lions develop a liking for human blood. It will be a nightmare.”

Noting that people have largely cared for and accepted animals in Amreli, Aniruddh Pratap Singh, Chief Conservator of Forests, Junagadh, says, “We are ready to help build sheds or tents so that labourers don’t have to sleep in the open.”

Govind Patel advises the Forest Department to also notify new lion corridors and deploy more manpower in Amreli, as well as minimise the man-animal conflict through public awareness.

However, he voices what many of them fear. “Whether people will accept the presence of lions now that they have started attacking humans is a big question.”

***

Over at Ambardi village, it is 8.30 pm, and Raju and family close the iron gates of their pucca cottage, locking in their dozen goats, a buffalo and Pancha’s dogs Kalo and Jado, while spreading their rugged quilts on the ground in the open.They have no cots, Raju says, as he prepares for a nervous night in the open. Apart from them, the only ones out in the darkare the family’s seven chicken, huddled under a tarpaulin-covered structure.

A couple of such nights later, the entire family of six moves out.

http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/gir-lion-pride-caged-2847872/