English language news articles from year 2007 plus find out everything about Asiatic Lion and Gir Forest. Latest News, Useful Articles, Links, Photos, Video Clips and Gujarati News of Gir Wildlife Sanctuary (Geer / Gir Forest - Home of Critically Endangered Species Asiatic Lion; Gir Lion; Panthera Leo Persica ; Indian Lion (Local Name 'SAVAJ' / 'SINH' / 'VANRAJ') located in South-Western Gujarat, State of INDIA), Big Cats, Wildlife, Conservation and Environment.

Tuesday, March 6, 2007

3 rare Asiatic lions killed in sanctuary in western India

http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/world/20070305-2202-india-lionskilled.html

3 rare Asiatic lions killed in sanctuary in western India

By Gavin Rabinowitz

ASSOCIATED PRESS

10:02 p.m. March 5, 2007

NEW DELHI – Poachers killed three highly endangered Asiatic lions in their only remaining sanctuary in western India, removing their claws and bones and raising fears for the future of these rare cats, wildlife officials said Tuesday.

Rangers at the Gir National Park in the state of Gujarat found the mutilated bodies of two lionesses and a cub on Saturday deep within the park, said Bharat Pathak, the park's conservation officer.

Only some 350 of the Asiatic lions that once roamed across much of Asia from Turkey to India still exist, all of them in the Gir park. The killings sparked renewed calls from conservationists to set up an alternate sanctuary.

The poachers left the pelts of the lions, taking their claws, bones and skulls – which are highly prized in traditional Chinese medicine – raising fears that a professional gang of poachers was behind the killings, Pathak said.

The department has announced a reward of $1,120 if “someone can give a clue about who killed the lions,” he said.

While several of the lions have been killed in recent years, this is the first case of poaching inside the protected area. Other lions have been poached when they strayed outside the park or were killed by angry villagers after the lions took their cattle. Hundreds of open wells in the area also act as death traps for the lions.

“This is of particular importance because it happened right inside the park,” said Belinda Wright of the Wildlife Protection Society of India.

Pradeep Khanna, the state's Chief forest officer, said that a request had been made to the government to step up security on India's borders to prevent the body parts from being smuggled out of the country. Park patrols also would be stepped up, he said.

“We will review our security arrangements,” he told the CNN-IBN news channel.

Protection for wildlife in India is notoriously lax. Parks do not have enough rangers to keep out poachers. Villagers are often allowed to live within sanctuaries, which leads to growing conflicts between the local populations and animals – particularly tigers, leopards and elephants.

Even a national outcry and a commission set up by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2005 in the wake of revelations that poachers had wiped out every tiger in Sariska, one of India's premier tiger reserves, has failed to stem the killings.

The killings of the lions raised fresh calls to set up a second lion sanctuary. Conservationists fear that keeping all the lions in Gir makes them particularly vulnerable to poaching and disease.

“All big cats are very susceptible to feline diseases,” Wright said. “They get hit by disease that runs through the whole population and there is nothing you can do.”

In 1972, the government declared the Gir National Park a protected sanctuary for the Asiatic lion, which can be differentiated from the African lion by a characteristic skin fold on its belly.

Males also have thinner manes.

However, the government has not succeeded in relocating the thousands of people who live in the forest reserves. The 460-square-mile sanctuary is home to at least 4,000 people and is crisscrossed by a railway track and five roads.

The Indian government has set up a second sanctuary for the lions in the central state of

Madhya Pradhesh, but the state government in Gujarat has refused to send any of the lions there, saying they were a symbol of Gujarat.

“This issue has nothing to do with the issue of relocation of lions,” Khanna told the Times of India newspaper. “Relocation is not under discussion,” he said.

3 Gir lions poached, bones and claws ripped by Haresh Pandya in Hindustan Times

http://www.hindustantimes.com/news/181_1945057,000900040003.htm

3 Gir lions poached, bones and claws ripped

Haresh Pandya

Rajkot, March 5, 2007

In what is regarded by nature lovers and wildlife activists as the most gruesome incident of the animal killing in the history of Gir forests in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat, two lionesses and one lion were brutally killed by some unidentified poachers. Their decomposed carcasses were recovered by forest officials and, worst still, all their bones and claws were ripped off.

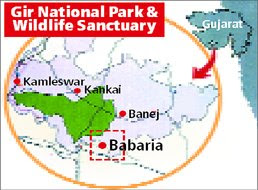

"We came across extremely degenerated carcasses of two lionesses and one lion from the Babariya Range on March 3. Many scattered pieces of their flesh were recovered from the spot. But all their bones and claws were missing. Obviously, they were killed by some unidentified professional hunters," chief wildlife warden Pradeep Khanna told Hindustan Times on Monday.

"We have registered an offence against the unnamed killers under different sections of the Wild Life (Protection) Act 1972. We have initiated a thorough inquiry into the incident. We have launched a manhunt and alerted the police to keep a strict vigil at every exit point from Gujarat. We have also announced a cash prize of Rs 50,000 for anyone giving information about the poachers involved in this heinous crime," added Khanna.

"No professional gang of poachers has ever been found in Gir. Although there have been odd incidents of a lion or two being found dead in a suspicious manner, it is usually due to some accident or injury. I really do not think poachers are operating from Gir. But this particular incident, when three lions have been found killed together, makes us a bit suspicious now. Rest assured, we will spare none and take stringent actions against those involved in hunting the big cats," said Khanna.

In all, a lion is born with 18 claws. It means the poachers fled with all the 54 claws after killing two lions and one lioness.

A lion claw, among other things, is regarded as an article of jewellery by certain communities. There is a huge demand for the lion claws in the international market, too. A lion claw fetches anywhere between Rs 10,000 and Rs 20,000. The skin of lion, just like that of the tiger, is also considered invaluable by many people with special tastes. They are said to be ready to offer any price for such stuff.

This is also what makes poachers to execute their deadly designs. They generally lurk on the sanctuary's fringes, where the big cats venture out frequently to prey on the livestock belonging to settlers on the outskirts of Gir. Their standard method is to poison the kill and then just wait for the lion to die.

In September 2005, too, the Gir officials had recovered three carcasses, including two burnt ones. They had subsequently raided a temple near Hirava in Gir and caught three men in the possession of 31 claws and a large lion tooth. Following detailed reporting by Hindustan Times, the Ministry of Environment and Forests had ordered the Gujarat government to conduct an inquiry into the death of lions in Gir forests and submit a report in a week.

In the latest incident, however, the poachers simply butchered the lions, probably after poisoning them or shooting them, and removed their bones and claws. The carcasses were in such a degenerated condition that postmortem was just not possible.

"The Gir authorities should hang their heads in shame because the three lions were killed only 500 metre from the Babariya Range office, where a certain number of officers and forest guards are supposed to be doing duty round the clock, and hardly 200 metre from the state highway.

Obviously, such a thing cannot be possible without support of some forest officials. Chief conservator of forests Bharat Pathak, who has not been transferred since last six years for mysterious reasons, is solely responsible for this incident. He, along with some other officials and supervisors, ought to be suspended immediately," said Amit B Jethava, president, Gir Nature Youth Club, in his letter to the Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi and forest and environment minister Mangubhai Patel on March 5.

A copy of this letter, in which Jethava has mentioned in no uncertain terms many startling goings-on in Gir thanks to certain forest officials, is in possession with Hindustan Times.

In first for Gir, two lionesses, cub killed; forest officials say poachers at work by SIBTE HUSAIN BUKHARI

Link:

http://www.indianexpress.com/story/24865.html

Print Story

In first for Gir, two lionesses, cub killed; forest officials say poachers at work

SIBTE HUSAIN BUKHARI

Posted online: Tuesday, March 06, 2007 at 0000 hrs IST

JUNAGADH, MARCH 5 Two lionesses and a cub were killed by poachers inside the protected area of the Gir sanctuary, forest department officials said on Monday.

They say this is the first time it has happened within the protected area, though there have been instances of lions being poisoned or electrocuted in areas around the sanctuary.

The claws and bones of the three cats are missing and it is suspected to be the handiwork of professional poachers. Chief Conservator of Forest (Wildlife) Bharat Pathak said: “Prima facie, this seems to be the work of professional hunters, not locals.”

The mutilated carcasses of the big cats and a cub were found on March 3, and the incident may have occurred around March 1, forest officials said.

The department learnt of the killing from an informer, who told officials he had seen the carcasses lying on the Babaria-Una road, which passes through the Gir sanctuary and is open to visitors all day. The area falls under the jurisdiction of Jamwala Assistant Conservator of Forests headquarters in Gir (West) forest division.

A special investigation team has been formed by the Forest Department to probe the killings, and the Chief Wildlife Warden (Gujarat) has declared a reward of Rs 50,000 for information regarding the incident.

A special investigation team has been formed by the Forest Department to probe the killings, and the Chief Wildlife Warden (Gujarat) has declared a reward of Rs 50,000 for information regarding the incident.“Preliminary investigations have revealed that the lionesses and the cub were killed around March 1. The Forest Department was tipped off by an informer on March 3. Following this, Assistant Conservator of Forest (Jamwala) rushed to the spot and confirmed the finding,” said Pathak

“Apart from the claws and the skulls, all the bones have been found missing from the carcasses. This has led us to believe that professionals were involved,” said Deputy Conservator of Forest (Gir West) B L Shukala. “However, as pieces of skin have been found from the area from where the carcasses were discovered, it seems that animal skin was not what they were after.”

“A dog squad and a team of forensic experts completed searching the area by Monday afternoon. The sniffer dogs led the team to the roadside, and we suspect that the persons involved in the poaching escaped in a vehicle,” said Shukala. “We are expecting the FSL’s report in four-five days.”

The Forest Department also convened a meeting of sarpanches from Babaria, Jamwala, Talala and nearby villages on Monday afternoon for distribution of pamphlets declaring the reward for information on the incident, said Shukala. “A special investigation team comprising Jamwala ACF’s mobile squad and Talala ACF has been formed to probe the killings. The team will be led by Deputy Conservator of Forest (Gir West). The Conservator of Forest (Wildlife) will monitor the investigations,” said Shukala.

Though a protected zone, Gir lions have often been target of poachers. “A few years ago, a tribal gang from Madhya Pradesh had been arrested from Plaswa village ( around 10 km from Junagadh) and animal skin, feathers found in their possession,” said Bharat Pathak adding that of late, even locals have been targeting lions for preying on their livestock or villagers.

In August 2005, two persons were arrested from an ashram on charges of poisoning two big cats,” he said.

Monday, March 5, 2007

A kingdom too small by DIONNE BUNSHA

DIONNE BUNSHA

Photographs: Ashima Narain

Lions in Gir look for new territories as the sanctuary is not large enough for their population.

A LION prowling on the beach? Yes, small groups of the world's last surviving Asiatic lions have moved out of the Gir sanctuary in Gujarat's Saurashtra region towards the coastal forests of Diu. They have not disturbed any sunbathers so far. Nor have they attacked people in the coastal villages. The Gir Protected Area (GPA) is simply too small to hold the 327 Asiatic lions that the planet has in the wild, so the younger ones have moved out in search of new territory - as far as Diu, around 80 km away.

The Asiatic lions of Gir are the world's last surviving group of the sub-species in the wild.

"It may seem unusual to find a lion on the coast, but this is not the first time that they have reached the shore," said Bharat Pathak, Conservator of Forest (Wildlife), Junagadh. Lions were spotted in the coastal areas in the early 1900s, according to the Junagadh Gazetteer. Now, as the lion population is larger and open grasslands are shrinking, the animals are dispersing as if to reclaim the 2,560 sq km they inhabited until 1956. The GPA is only 1,421 sq km of dry, deciduous forest, a little more than half the original size of the forest. There are fights for territory between lions. The weaker ones step out. There are now three or four lion populations outside the protected area. A pride of 13 lions lives in the Girnar hills, 20 roam the coastal areas, there are 16 in the Hipavadli-Savarkundla region and seven in other places.

The number of lions has exceeded the sanctuary's estimated carrying capacity, according to Dr. Ravi Chellam, an expert on the Asiatic lions in Gir. Chellam's survey, conducted while he was with the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), recommended that the lions be shifted to Kuno, a forest in northern Madhya Pradesh, more than 1,000 km away.

Lions do not shy away when they encounter humans. This often allows close shots.

"Just because their population has increased in the last two decades does not mean that the long-term future of wild Asiatic lions is secure," says Chellam's report for the WII. "If restricted to a single site which is relatively small in size, the lions face many extinction threats - genetic and environmental. Catastrophes like an epidemic could result in the extinction of an endangered species." The WII report points out how a canine distemper epidemic in the early 1990s at the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania affected 75 per cent of the lions and killed 30 per cent, even though there was a large lion population spread over a vast area. "If a similar epidemic were to affect the lions in Gir, it would be very difficult to save them from extinction, given the much smaller area and relatively smaller lion population," says the report.

The WII suggested `preparing' 400 sq km of the 3,700 sq km Kuno forest for the Asiatic lions. The Central government has accepted the recommendation. `Preparing' this area for the lions means moving out villagers who live there and building up a `prey base' for the big cats to feed on. The government has decided that around 7,400 people in 19 villages will have to be moved out to make way for the eight or so adult lions and their young, who will be brought here once the prey base is adequate. Several villages have been relocated outside the

forest.

However, the Gujarat government is reluctant to move any of the lions out of the State. It wants the lions to remain uniquely `Gujarati'. "Rather than moving the lions so far away from Gir we are planning to shift some lions to Barda, a sanctuary near Porbandar," said Pathak. Gujarat's Conservator of Forest (Wildlife) Pradeep Khanna said that an alternative location for the lions was not a good idea. "We are facilitating the expansion of the lion's home zone. There is no need to relocate them. Re-introduction of a carnivore in a new environment is not so easy. An earlier effort had failed. Moreover, there are tigers in the Kuno forest. When natural dispersal of lions is taking place around Gir, why interfere with nature?" he said.

However, several wildlife experts disagree. Ravi Chellam said: "The Gujarat government has successfully increased the number of Asiatic lions. But we need to manage that success and think long term. It is better to avoid risk. How would it hurt if just five or eight adults are removed from the population? Their positions are misinformed. They say it is dangerous for the lions to be in tiger territory. But just eight tigers in Kuno pose no grave threat. The lions came to India and settled in the same north-central forests where tigers lived. They co-existed in the past, maintaining an uneasy truce. Lions live in the dry grasslands, whereas tigers move in the thick, dense forest."

While the disappearance of India's tiger population raises a national outcry, the gentler Asiatic lion's fragile existence does not cause the same alarm. India has 3,000-odd tigers in 27 reserves. But there are only 327 Asiatic lions (according to the last lion census in 2000) confined in only one small sanctuary, Gir.

The Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) is somewhat different from its African cousin in genetic make-up, skeletal structure and appearance. The Asiatic lion is smaller, has a loose fold on the belly, rarely seen in the African animal, and its mane is less dense. Asiatic lions were once spread across the Asia Minor and Arabia; they migrated to India through Persia. In the Indian subcontinent, the range of the Asiatic lions once extended across northern India, as far as Bihar and Orissa in the east, with the Narmada river marking the southern limit. Before the close of the 19th century, the Asiatic lion had become extinct everywhere except in Gir. The last lion surviving in the wild outside Saurashtra was reported in 1884.

Ironically, one of the first to rescue the lions from extinction was a shikhari (hunter) - the Nawab of Junagadh, a princely state in Saurashtra.. At the turn of the 20th century, he was shocked to find that there were only 12 lions left in the grassland. He declared a ban on lion-hunting and ensured that the big cats were protected. After his death, the British administration tried to control hunting in the forest.

The first lion census was conducted in 1936, which put the estimated strength of the lion population at 287. The number dropped to 177 in 1968, because the animal's grassland habitat was shrinking. In 1965, the government started the lion conservation programme and declared the area a sanctuary. Since then, the lion population has been growing steadily. A fresh census is now under way.

Pathak explained why the lions managed to survive in Gir: "The last few lions remain in Gir because it is a compact, unfragmented ecosystem. And, since the time of the Nawab of Junagadh, there have been continuous conservation efforts here. Moreover, the local people respect nature and our staff work hard to preserve the forest."

However, conditions for survival are not exactly perfect within the small confines of the Gir sanctuary. Five State highways and a railroad pass through the forest, which also draws 2.5 lakh tourists every year. The three big temples in the forest, which has 23 shrines tucked away amid the trees, draw more tourists than the wildlife safaris do. There is widespread limestone mining in villages just outside the sanctuary. There is a cement factory 15 km away from the protected area. This destroys the natural habitat and drains forest resources, including water, so precious during the dry months. Water holes within the sanctuary are drying up, pushing lions out in search of both water and prey.

Watering holes are also places where it is easier to find prey like deer and the Nilgai. Recently, lions have fallen into wells in the villages on the outskirts of the forest. Instead of tackling these problems, the government is intent on getting rid of the Maldharis, local herdsmen who have co-existed with the lions in the forest for centuries.

The Maldharis live in small settlements, each called a `ness'. There were once 129 nesses in the forest. The lions often prey on their cattle, but the Maldharis are not aggressive towards the animals. They accept it as part of nature's cycle. The government offers them Rs.5,000 as compensation, but claiming it entails a long and tedious engagement with the bureaucracy.

In 1972, the government tried to relocate some nesses outside the sanctuary. It shifted 580 of the 845 Maldhari families living in the forest. Though they were given land, the Maldharis did not do well as farmers. Many sold off their land. Today, there are 54 nesses (400 families) inside the sanctuary.

Most Maldharis prefer to settle in the forest, even if it means living in small, secluded huts, without minimal amenities like electricity or water supply, and with poor access to markets, schools and hospitals.

Dadhiya ness, which had 50 people, was shifted in the 1970s. Now only 12 families remain. "We didn't go to the new land, only half our family moved out. The land they gave as compensation was stony, you can't farm on that land," said Jaggo Ruda Jatwa. "We have 25 head of cattle, so we stay here. There's nothing for us outside the sanctuary. What will we feed the cattle? We don't know farming."

The nilgai, the spotted deer or chital constitute the main wild prey base of the Asiatic lion.

But experts question the Forest Department's priorities. "Relocating the Maldharis is not going to solve the problem. It is more important to translocate the lions," Ravi Chellam said. "For the survival of the lions, the Maldharis are not an issue. Lions can coexist with humans. You need to be careful while relocating people. Wildlife conservation need not be purist."

Both the Maldharis and the trackers, who live in intimate connection with animals, have detailed knowledge of the forest. A tracker who has known the forests long and closely said the lions would not survive without the Maldharis. "The Maldharis and their livestock are essential to the forest ecosystem. Yes, the cattle eat grass, but without their droppings, how will the grass grow? They are not competing for grazing space with other lion prey like deer, who mainly eat leaves."

Ravi Chellam, however, believes that the lions can survive without the Maldharis. Lions started feeding more on wild prey (mostly the chital deer) after Maldhari villages relocated and livestock to prey on became scarce. "Over the years, the number of wild prey animals increased dramatically after some Maldhari villages were relocated and the national park was created. Gradually the lions have changed from being mainly livestock feeders to wild prey feeders."

But the tracker insists that the lions prefer livestock even though there are so many more deer now. "After the Maldharis moved out, the lions also moved beyond the outskirts of the forest because there were more human settlements with cattle there. The last census found fewer lions in the core national park area than in the sanctuary surrounding it." Ravi Chellam says that the lions are moving out of the sanctuary because of a lack of space rather than food.

As the debate continues on what is best for them, the kings of the jungle seem to be moving out to regain lost territory. If humans cannot make place for them, they seem to be carving out their own spaces, even on the beach. But that alone may not save the species. Some have to be moved much further than the beach.

(This is the first in a two-part series on the issues concerning the existence of the last surviving Asiatic lions. The next part will look at the displacement of Adivasis in the Kuno forest, Madhya Pradesh, to make way for the translocation of the Asiatic lions.)

Thursday, March 1, 2007

On the lion trail by DIONNE BUNSHA

Source:

http://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/mag/2005/06/05/stories/2005060500110200.htm

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Magazine

EXPERIENCE

On the lion trail

DIONNE BUNSHA

The last of the Asiatic lion species is still in Gir because it is a compact, unfragmented ecosystem. But there is a danger that it could be wiped out if disease strikes.

PHOTO: ASHIMA NARAIN

SOMETIMES, even the open forest can get too crowded. Well, at least for the Asiatic lion in Gir. Their expanding population finds the existing Gir National Park too small, and younger lions are getting out of the protected area, right up to the coast near Diu, 80 km away.

Gir is home to the last surviving population of the Asiatic lion. That makes it pretty unique. Don't expect thick jungle with tall green trees. The dominant colour here is brown. It's 1,421 sq km of dry, deciduous forest and grasslands — dry being the key word here. The lion shares the forest with the leopard, the chital, the jackal, the wild boar, the peacock and the Maldharis, local herdsmen who have co-existed with the lions inside the forest.

For a population that's growing, it's still not easy to find the lions. Even though they are supposed to have reached Diu, you're not likely to see them prowling on the beach. Finding them inside the national park, where safaris are allowed, is difficult enough. You could drive around in an open jeep for hours seeing endless numbers of deer, chital and peacock, but there won't be any sign of a lion. They aren't shy of human beings. They're just lazy. They'd prefer to sit in the shade and come out to hunt only in the late evenings or at dawn, when it's cooler. For those who don't have the patience or didn't have much luck seeing lions in the wild, there's always the Gir Interpretation Zone at Devalia, 12 km from Sasan, an enclosed area where some lions are kept for breeding and tourism. You are packed into a bus and driven around the enclosure, and there's no way you can miss seeing the cats.

To spot a lion in the forest, it's best to set out on a safari as close to dawn as possible, or hang around in the evening safari for as long as you can. Every morning, the forest department sends out its trackers to search for lions. So, it's better to try and keep in touch with the trackers so that you will know if a lion has been spotted on a particular route. Chatting with trackers will also give you an idea about where lions were seen recently and where they are likely to be found the next day. The lions are so familiar with trackers that they can sometimes identify them, allowing them to get close and even treat their wounds.

We were lucky enough to come across a tracker who had just spotted a lioness off the course of the road. So, we hopped off the jeep and walked down a small ravine. There she was, calm and majestic, not in the least bit perturbed by a bunch of tourists staring at her, taking photographs wildly without pausing. She coolly strutted towards us, then turned to the side and sat under a tree. Unlike the tiger and the leopard, the lion is not elusive and rather comfortable around human beings. A pride just couldn't care less, as long as you keep your distance. Often, it circles a Maldhari ness (settlement) and preys on their cattle. The Maldharis are used to it, accepting it as part of nature's cycle.

Asian and African

The Asiatic lion (Panthera leo persica) is different from the African lion in its genetic make-up, skeletal structure and appearance. It has a loose skin fold on the belly and its mane is less dense. The Asiatic lion once roamed the forests of Asia Minor, Arabia, Persia and India. It lived in the forests of northern India as far to the east as Bihar and Orissa, with the Narmada river marking the southern limit. By the 1880s, it had become extinct in the rest of India except Gir.

The last of the species is still in Gir because it is a compact, unfragmented ecosystem. And, since the time of the Nawab of Junagadh, there have been continuous conservation efforts here. The Nawab was shocked to find that only 12 lions remained in the grassland. In the early 1900s, he declared a ban on lion hunting and ensured their protection. The last census in April this year reported 359 lions, the highest-ever count. It's still an endangered species but over the years, numbers have been increasing. Yet, scientists feel that the species is in danger if the entire population is located at one place. If an epidemic strikes, the species could be wiped out. That's why a pride is to be shifted to a sanctuary in Kuno, Madhya Pradesh. But the Gujarat Government won't let it leave the State.

* * *

Out of Africa?

GIR isn't only about the lion. There are other interesting places around as well.

En route from Rajkot, you can stop at Junagadh, a historic city with Ashoka's Buddhist monuments, Hindu and Jain temples, mosques and the Junagadh fort. It's flanked by Mt. Girnar, where the highlight is the Shivratri festival every year. Here, thousands of sadhus congregate for nine days of festivities.

Just two hours away is Gujarat's watering hole, Diu — a quaint little Portuguese island where alcohol-parched Gujaratis escape prohibition. Also living close to Diu are the Siddhis, a tribe of African origin, with a very distinct culture and music.

With the Siddhis and the lions, this western tip of Gujarat is perhaps the closest to Africa we will get.

© Copyright 2000 - 2006 The Hindu