As

the convoy of elephants trundled their way through the dew-laden

grasslands in Kaziranga National Park, I came across a pair of

one-horned rhinos gently grazing in the elephant grass. This was my

first rendezvous with rhinos, in their natural habitat. Built like a

battle tank on stubby legs, the rhino is the star attraction of the

park. From my lofty vantage point on elephant back, besides the

endangered one-horned rhinos, I spotted wild water buffaloes, hog deer,

and also hundreds of swamp deer trot past wild boars before they

retreated into the high vegetation. This wildlife Eden also shelters

hoolock gibbons, tigers, leopards, capped langurs, sloth bears, jackals,

and pythons. It is also the most beautiful national park in the

subcontinent, with superb ponds, lakes and rivers where otters frolic

and herds of elephants splash around.

Lower

down, in West Bengal, as the boat cruised through the muddy estuaries

and mangrove forests in the Sundarbans National Park, my eyes kept

peeled for the tigers which are rarely seen but always sensed. Sprawling

over 26,000 sq km, it is the largest single tract of a unique mangrove

ecosystem in the world. Water bodies crisscross the forest and separate

the hundreds of islands that dot the delta. Here, in the tangle of

mangrove roots, a unique mid-world between sea and land, I saw only

saltwater crocodiles and mudskippers (fish that climb tree). These are

among the many wonders of this wild paradise. Travelling across the

mangrove-lined backwaters of Sunderbans and communing with nature at its

rawest level was itself an unforgettable experience!

To

experience Kipling country, I visited Madhya Pradesh, Kanha, Pench and

Bandhavgarh which provide among the finest wildlife experiences

available on earth. Bandhavgarh is also steeped in history, myths and

legends besides playing host to a bewildering variety of animals. As

Bandhavgarh flaunts the largest density of tigers in the country, it is

seldom that one returns from Bandhavgarh without seeing a tiger emerging

out of the tall grass, or pursuing the pugmarks crossing the jeep

tracks. I had my first darshan of a tiger in the wild here. It was an

experience that was both magical and mysterious. The bird life here is

no less astounding, with as many as 250 species of nesting in the park,

including the stately adjutant stork. In Kanha and Pench I went on

wildlife safaris scouting for the Sher Khans, but luck was not on my

side. My wildlife jaunts took me to Gir Forest, where I had my first

fleeting glance of a lion and lioness lolling a few feet away from the

jeep.

Down south in Kerala, I

followed the footsteps of the nimble-footed Nilgiri Tahr, a highly

endangered animal, listed in the IUCN Red Data Book, which lives in

herds on the steep black rocky slopes of the mountains of Anaimudi in

the Eravikulam National Park. About one-third of the world's population

of Nilgiri Tahr reside in these emerald grasslands. In 2006, I witnessed

in this unique ecosystem the spectacular blooming of Neelakurinjis.

At

Periyar Tiger Reserve, I had glimpses of nature's wonders while the

boat glided along the picturesque Periyar Lake, the sanctum sanctorum of

the reserve. I sighted elephants ambling along the banks of the lake,

gaurs grazing peacefully on the grasslands along the wooded waterfront,

darters and cormorants drying their wings perched on the ghostly

deadwood protruding from the lake. This reserve is synonymous with

Asiatic elephants, but sightings of tuskers have become very rare.

This

wildlife haven also houses several endangered species like the

lion-tailed macaque, small Travancore flying squirrel, Salim Ali's fruit

bat, and the rarely sighted Nilgiri Marten. Though there are more than

40 tigers in the reserve, they are rarely sighted. Of the 160 species of

butterflies spotted here, the Travancore evening brown, one of the

rarest butterflies in the world, was spotted here after a gap of several

decades.

A community-based

ecotourism initiative originated in this blessed place where

rehabilitated poachers-turned-forest protectors earn their livelihood as

guides and facilitators. I was lucky to witness the Chitra Pournami

festival at the scattered ruins of the ancient Mangala Devi Temple that

forms a part of the core area of the reserve. The forest road to Mangala

Devi is open only once a year to the public when pilgrims from Tamil

Nadu and Kerala congregate to offer worship to this deity.

Valued ageing

In

Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuary, the sight of Kannimara Teak, the

world's oldest and largest teak tree (girth of 6.57 m and a height of

48.5 m), left me gaping in wonder. It takes five adults to encircle it

with their hands outstretched. This living relic of the once-luxuriant

natural teak forests was awarded the Mahavruksha Puraskar by the

Government of India in 1994-95. In this unique wilderness area I saw

three dams that serve as freshwater storage reservoirs, and the first

ever scientifically managed teak plantation. With a rich diversity of

bird life, Parambikulam is a great birding getaway, once the favourite

haunt of ornithologist Salim Ali.

Located

along the western corner of the Nilgiris in Palakkad district, the

Silent Valley National Park deserves a special mention as it came into

the limelight in the 1970s, when the government planned to dam the

river. The protests that followed were the beginning of the

environmental movement in India. And the entire valley was declared a

national park in 1985. It is one of the last vestiges of undisturbed

tropical evergreen rainforest which covered most of the Western Ghats.

Ecologists call it an 'ecological island', one that boasts of a wealth

of biological and genetic heritage. It is called the Silent Valley, yet I

could hear it throbbing with the sounds of the forest.

There

is an incredible number of sanctuaries and parks that I have not

journeyed to. Ranthambore National Park, which is widely regarded as one

of the best parks for tiger sightings, is one of them. Tadoba also has

become a hotspot for tigers. Each national park has its own signature

wildlife. In Tamil Nadu, the lesser-known Mudumalai National Park,

Kalakad-Mundanthurai, Point Calimere can provide unending delight and a

variety of experiences to nature enthusiasts. From Chennai, every

January, I used to go to Vedanthangal, the oldest water-bird sanctuary,

when it resonates with the melodious birdsong - of the winged visitors

of exotic plumage. Other winter havens for migrants are Point Calimere

and Pulicat Lake where large flocks of flamingoes can be spotted.

Karnataka

boasts of some of the largest jungle tracts south of the Vindhyas. From

the majestic evergreen forests of the Western Ghats to the scrub

jungles of the plains, a wide variety of habitats teem with diverse

flora and fauna. Bandipur, Bhadra, BR Hills, Nagarhole, Kudremukh and

Kali tiger reserves boast of admirable heterogeneity of faunal heritage.

Though elephants take the lead role in Bandipur and Rajiv Gandhi

national parks, it is also the land of roars. Photographers troop to

these reserves to capture wildlife in close proximity. Ranganathittu is

my favourite bird sanctuary where I have experienced the thrill of a

boat ride that took me within touching distance of the birds.

Kokkarebellur, where pelicans and painted storks live in harmony with

villagers, is claimed to be one of the best among the 46 community

reserves in the country.

The

genesis of Indian wildlife can be traced back to the days of yore when

royalty used the jungles as their hunting ground. They had an

unsurpassed communion with wildlife. Bandhavgarh was once the shikargarh

of the maharaja of Rewa. The Baghel Museum has on display ancient

hunting equipment used by him. Even late Rajmata Gayatri Devi, the

maharani of Jaipur, indulged in hunting, right from the days she was the

princess of Cooch Behar, a state in North Bengal, which perhaps has an

unrivalled record of big game shooting in all of eastern India. The

Keoladeo Ghana preserve was created by the maharaja of Bharathpur at the

turn of the century to attract migratory birds, which he and his guests

took pleasure in shooting! Even the venerable forest of Bandipur was

once the private hunting ground of Mysuru's royalty. In Mughal and

British India, tigers were hunted for prestige as well as for taking as

trophies. During the reign of Mughals, efficient hunters were awarded

titles such as 'Hunt Master', and in the first phase of the reign of

East India Co, tiger hunters were highly rewarded. Subsequently, many

hunters turned into conservationists.

Wildlife first

Wildlife

conservation in India through dedicated parks started with the Jim

Corbett National Park in 1936. India's first national park was

established in 1936 in Uttarakhand as Hailey National Park, which was

later rechristened as Jim Corbett National Park. The rich saga of Indian

wilderness, started by the legendary Corbett, continued. By 1970, India

only had five national parks. In 1972, India enacted the Wildlife

Protection Act to safeguard the habitats of endangered species. Project

Tiger was launched by the Government of India in 1973 to save the

endangered species of tigers in the country. Starting from nine reserves

in 1973, currently, the number of tiger reserves is 50, with a total

area of 71,027.10 sq km. Tiger population, as per the last census, is

2,226. Further, federal legislation strengthening protection for

wildlife was introduced in the 1980s. As of July 2017, the number of

national parks has burgeoned to an impressive total of 103, encompassing

an area of 40,500 sq km, comprising 1.23% of India's total surface

area. The number of wildlife sanctuaries has increased to 544.

Quite

a few important faunal habitats have gained recognition after their

inclusion in the 'biosphere reserve' and the 'world heritage site'

programmes. However, many species of the wild fauna and flora still

remain greatly endangered, and so do their habitats. The loss of these

fragile habitats is counterproductive to wildlife conservation efforts.

Equally disheartening is the poaching activity rampant throughout the

country, made worse by matters beyond the control of conservationists.

The introduction of site-specific innovative conservation measures will

help save many endangered species.

The

wildlife movement has caught the fancy of people, and wildlife tourism

is growing by leaps and bounds, something that could not really have

been envisaged when the first national park was declared around 1935.

The need of the hour is not tourism control, but tourism management.

Concerted efforts should be made to divert the attention from

tiger-centric tourism, which has become the norm in our national parks. I

have seen overenthusiastic drivers embark on 'tiger-chases'. Tiger

fixation leads to a bizarre concentration of vehicles, which often

causes distress to the beleaguered animal, besides destroying the

serenity of the forests. One has to break the mould and concentrate on

other equally interesting denizens of the forest such as small mammals,

birds and butterflies through ecologically sensitive means.

From

this World Wildlife Day, celebrated on March 3, whenever we visit a

sanctuary, let's remember that we are guests in the animal's habitat,

and that we have to be quiet, considerate, and respect our hosts and

their space.

http://www.deccanherald.com/content/661318/walk-wild-side.html

Every year London Zoo count all the animals in the zoo to make sure

everyone is accounted for. All the keepers get involved in counting all

the species that live there. Now, we all know lemurs are clever but does

this keeper think they can use an abacus? Come on!

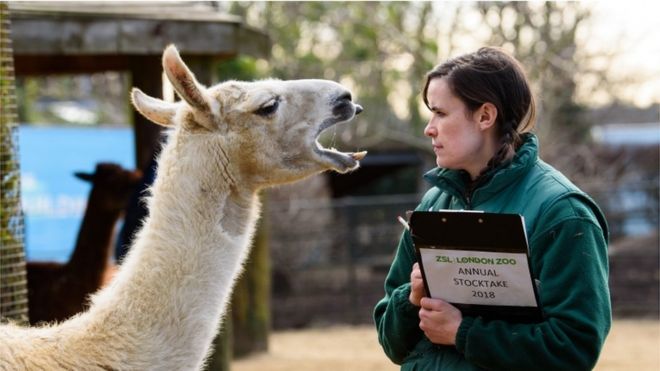

Every year London Zoo count all the animals in the zoo to make sure

everyone is accounted for. All the keepers get involved in counting all

the species that live there. Now, we all know lemurs are clever but does

this keeper think they can use an abacus? Come on! This llama looks like it has

plenty to say, doesn't it? Wonder if it's telling tales on the giraffes?

The keeper doesn't look scared though, she looks more like she's

inspecting its teeth? Hope there isn't any bad breath going on there...

Llamas live mostly in South America and they are very social animals and

live with other llamas as a herd.

This llama looks like it has

plenty to say, doesn't it? Wonder if it's telling tales on the giraffes?

The keeper doesn't look scared though, she looks more like she's

inspecting its teeth? Hope there isn't any bad breath going on there...

Llamas live mostly in South America and they are very social animals and

live with other llamas as a herd. Watch out! These squirrel monkeys look like they're messing with the

count numbers. Squirrel monkeys live in the tropical forests of Central

and South America in the canopy layer. They use their busy tails for

balance.

Watch out! These squirrel monkeys look like they're messing with the

count numbers. Squirrel monkeys live in the tropical forests of Central

and South America in the canopy layer. They use their busy tails for

balance. "Will you penguins just sit

still!" How is this keeper supposed to count these guys when they keep

running around? I don't think showing them a bucket of tasty fish will

stop them running around on their Happy Feet! Look - one of them is

trying to grab a sneaky snack!

"Will you penguins just sit

still!" How is this keeper supposed to count these guys when they keep

running around? I don't think showing them a bucket of tasty fish will

stop them running around on their Happy Feet! Look - one of them is

trying to grab a sneaky snack! That's more like it. It's a bit more relaxing for the keeper - but how

do you keep track of which penguin is which? Did you know almost all

penguins live in the southern hemisphere, with only one species, the

Galapagos penguin, found north of the equator.

That's more like it. It's a bit more relaxing for the keeper - but how

do you keep track of which penguin is which? Did you know almost all

penguins live in the southern hemisphere, with only one species, the

Galapagos penguin, found north of the equator. I'm not sure I like the way

Max the eagle owl is looking at me there! He could be getting ready to

swoop! Most owls are nocturnal animals which means they hunt at night. I

wonder if Max is feeling as grumpy as Old Brown if he's been woken up

for a count during his beauty sleep?

I'm not sure I like the way

Max the eagle owl is looking at me there! He could be getting ready to

swoop! Most owls are nocturnal animals which means they hunt at night. I

wonder if Max is feeling as grumpy as Old Brown if he's been woken up

for a count during his beauty sleep? Looks like this queen of the

jungle is checking that the keepers have got their sums right. Asiatic

Lions mostly come from the Gurat province of India. They're endangered

and the Asiatic Lion Census in 2017 found just 650 animals in the wild.

Looks like this queen of the

jungle is checking that the keepers have got their sums right. Asiatic

Lions mostly come from the Gurat province of India. They're endangered

and the Asiatic Lion Census in 2017 found just 650 animals in the wild. Normally London Zoo do their count at the beginning of January. They

have over 19,000 animals at the zoo and over 700 species. This is the

first count they've done since a fire at the zoo in December 2017.

Normally London Zoo do their count at the beginning of January. They

have over 19,000 animals at the zoo and over 700 species. This is the

first count they've done since a fire at the zoo in December 2017.

Incidents of cows with monstrous horns knocking down pedestrians are on the increase. (Supplied)

Incidents of cows with monstrous horns knocking down pedestrians are on the increase. (Supplied)  Owners of many cow sheds complain of lack of funds, fodder and medical facilities. (Supplied)

Owners of many cow sheds complain of lack of funds, fodder and medical facilities. (Supplied) Many companies have donated huge funds to gaushalas or cow sheds. (Supplied)

Many companies have donated huge funds to gaushalas or cow sheds. (Supplied) According to Abdul Lakhani (left), the cow has always been an

effective tool for the Hindu right-wing led by the BJP to divide people

communally. (Supplied)

According to Abdul Lakhani (left), the cow has always been an

effective tool for the Hindu right-wing led by the BJP to divide people

communally. (Supplied)